This is the question I always get when I say I’m a translator. Sometimes, those asking are implying “Is it good? Do you use it?”; at other times, it rather means “Unemployed already?” But it’s a legitimate question! I’m quite a technophile (I mean, I’ve had a custom keyboard made!); why, as a translator, shouldn’t I use yet another translation tool?

For many reasons (and because I have the option not to; not everybody can, I’ll come back to it). Before I list them, I need to make something clear: I say “AI” (=artificial intelligence) because it’s the word used most frequently these days to designate the large language models (generative artificial intelligence tools, the most famous of which is OpenAI’s ChatGPT) and, to a lesser extent, neural machine translation (like DeepL). These are the “tools” I oppose. I have nothing against AI when it decodes the human genome, when it detects upcoming natural disasters, or when it makes me think I’m very clever in video games. I’m no technophobe, and I have a precise target in mind when I talk about AI.

This point being settled, here’s why I’m against AI in translation.

A mediocre tool

I’ll start by acknowledging my privileged position: the main reason why I don’t use AI, is that enjoy good working conditions as a translator. The publishers I work for pay decent wages, and I don’t work for translation agencies that drive prices down and push the use of AI. I have enough work, and I’m paid well enough to avoid having to always work faster in order to put a roof over my head and bread on the table.

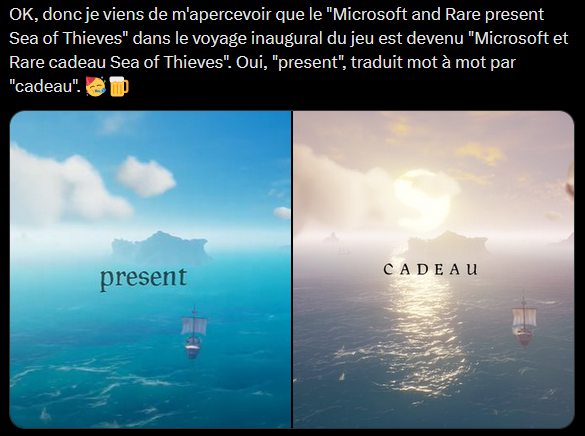

Therefore, why would I want to accelerate the translation process, when it is precisely this that gives me joy? Searching for the right word, reformulating a sentence ten times over to find the right phrasing, coming back to a text after letting it rest for a while and having that sweet eureka moment… I have no wish to precipitate any of this. Besides, in my fields of expertise (=books and video games), the supposed qualities of AI fall apart quite quickly. For a novel, it takes the form of consistency problems (one example among many others: in French, “tu” and “vous” being used interchangeably). Conversely, as is sometimes the case in video games, when you’re supposed to translate a few words that are incomprehensible without what shows up on the screen, AI has a hard time doing so, being unable to access this external context.

A very poor tool, then, and one I have no desire to use. Everyone should do the same, problem solved.

Of course, it isn’t that simple! Because those who hire translators and push for the use of AI in translation know perfectly well that it is a mediocre tool. But they don’t care, because their real interest lies elsewhere: better productivity. Translating more, faster cheaper. When translators are asked to do post edition, that is correcting what the machine generates instead of translating, it’s “only proofreading”, after all. It’s thus perfectly normal to halve wages. Never mind if post editing is a profoundly alienating task because errors follow no human logic. Never mind is the result is barely good enough because huge text volumes are dealt with in a very short amount of time. Never mind work conditions worsening. Things go faster. They make more money.

I could stop here, and simply point out that some unscrupulous clients promote AI to save money at the expense of the expertise, health and happiness of workers who find themselves forced to be blackmailed into doing post edition. It has happened before in other fields like technical translation, and no one escapes cost reduction. Not even those who adopt the rather despicable view that “literary translation” will never suffer the AI treatment because it is too noble a task (whatever that is supposed to mean). No one escapes cost reduction.

I could stop here. Sadly enough, AI has many more problems.

About training data

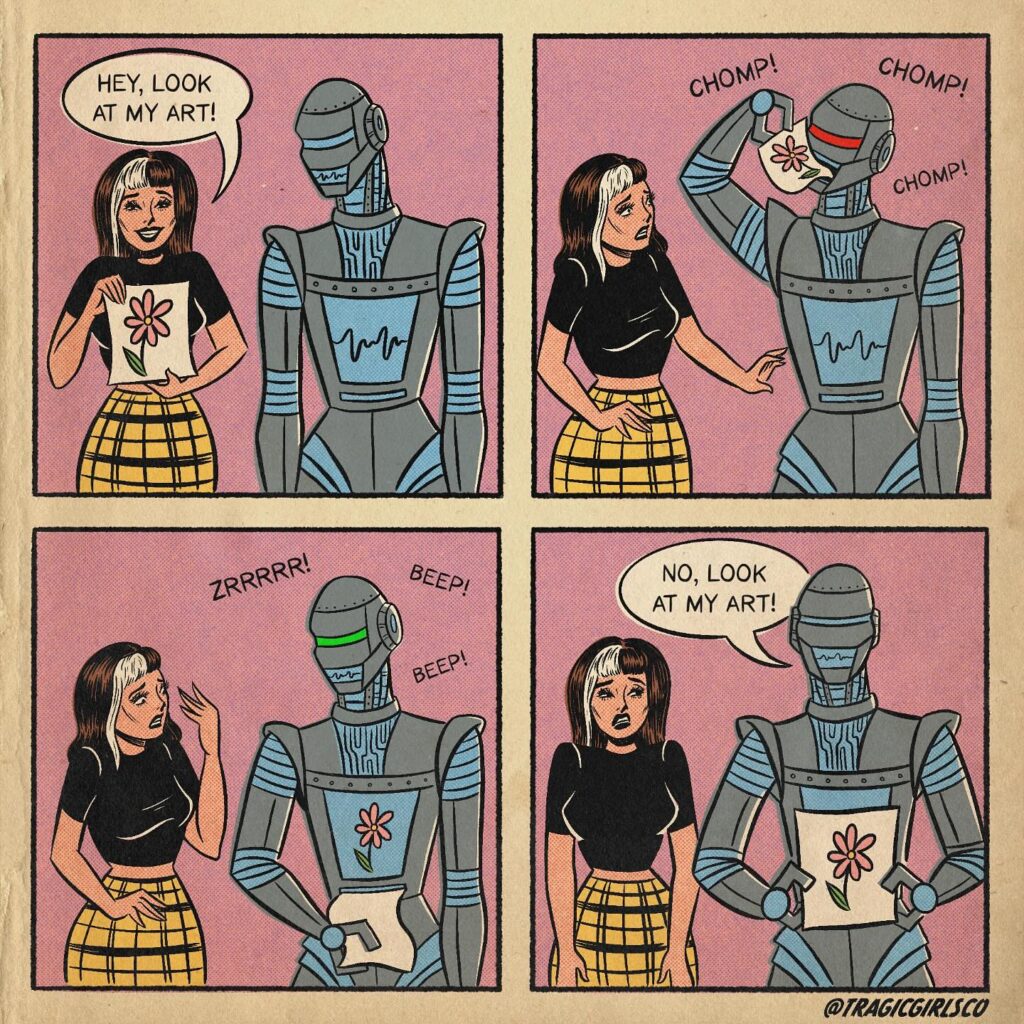

If we take a step back from the written word, there are many illustrators and visual artists who are staunchly opposed to the use of AI. It’s quite understandable: their work conditions are similarly worsened by AI, when jobs don’t simply vanish when a client decides, for instance, to have a whole corporate identity generated by AI. But that’s not all: there’s also the question of plagiarism.

How can a machine plagiarise anything? To understand this, we have to make a little aside on how AI works. Fundamentally, these are probabilistic machines: an AI displays, segment by segment, the most likely follow up to a given prompt. How does it determine what is likely or not? By having digested humongous quantities of data, which it analyses by trial and error thanks to computing power that is every bit as humongous. In a way, AI is the applied version of the infinite monkey theorem, according to which if you leave a monkey press the keys of a typewriter at random for an infinite amount of time, it will statistically end up writing Hamlet. If every last one of the billion computing units making up ChatGPT are one of those monkeys, there’s no need to wait for an infinite amount of time: you can get Hamlet pretty fast.

And although Shakespeare isn’t around anymore to complain we pilfer his famous tragedy, it’s not the case for all the artists whose data were used to train AI. Artworks have thus been nearly entirely reproduced, down to the artists’ signature, without their agreement. The OpenAI executives have argued this wasn’t supposed to happen but it did because it is difficult to know exactly what data AI was has been trained on. In other cases, they bragged about it, as when the company behind ChatGPT published an update allowing users to generate images mimicking the style of Studio Ghibli. And this was a calculated move: if ChatGPT can copy the style of one of the household names in animation, famous for valuing human know-how above all, then it can copy anybody’s. Artists are no match for the machine, they seem to be saying.

So that is indeed plagiarism: using data acquired without the consent of their authors, ChatGPT generates images shamelessly copying their style. And the same goes for text: ChatGPT uses some in the public domain, but also copyrighted material, that could very well end up in an AI-generated translation. You think you’re saving time, and you end up potentially infringing copyright law. And if you don’t explicitly forbid the machine from gorging on your work, it will be used without any qualms.

AI is thus a poor tool that can plagiarise the work of others, and that unbeknownst to the user, because there is no transparency at all on what data is used to train it. A rather sorry picture. And we haven’t talked about its energy cost.

A bottomless pit

You might have come across this very worrying figure: every short conversation with ChatGPT would consume 0.5L of water. It is disputed, and it is indeed difficult to know precisely how much is consumed for every prompt sent to the AI. Maybe this figure needs to be put in perspective? Maybe. What doesn’t need any perspective, is that AI companies are having nuclear reactors restarted/built to power their gargantuan data centres. What doesn’t need any perspective, is that those data centers are often built in already dry areas, thereby worsening the droughts its inhabitants already suffer.

It is tempting to say that, although it takes a lot to build it all today, once the infrastructure is finished we’ll be able to enjoy AI’s “advances” with a clean conscience. But that would mean forgetting the death cult of the AI promoters. Those are indeed first and foremost snake oil salesmen: they willingly promise that AI will lead to incredible scientific progress, lower the cost of life for all, and that, in an event called the “singularity“, AI will become a superior conscious being that will then be able to solve all humanity’s problems.

Maybe they believe in those promises, I can’t tell, of course. But it is way more likely that they are just a way to generate hype and raise capital to keep developing AI and, in so doing, to have OpenAI’s share price keep increasing. The next step is always a few million dollars ahead. And if you can fill the shareholders’ pockets trying to get there… well, there’s no harm in it, is there? As regards whether AI speculation will ever stop, I have no idea. What I do know is that the markets will always call for more growth, and thus for more energy consumption. Will the AI promoters act any different? I don’t believe so.

What is to be done?

As a conclusion, let’s go back to the beginning: no, I don’t and I don’t want to use AI for translation. Because it is a very poor tool, because it amounts to barely disguised plagiarism, and because it is an ecological disaster in the making which mainly exists to increase the profit margin of great technology companies.

That being said, it is absolutely not my intention to judge those who find themselves forced to use it, because their employer pushes post edition, for instance. Sometimes, you don’t have a choice: AI supremacy is so often presented as an irresistible future that many of our clients and bosses are fooled by it, more or less willingly. It is also a self-fulfilling prophecy: if a CEO is convinced that AI will replace their employees, they will terminate people to adapt to the coming of AI and… incredible! AI will have replaced their employees.

But for all the others, for all those who are not (yet) victims of AI-induced-unemployment, there is only one course of action: outright refusal to use this so-called tool. Polish up your talking points by reading on the topic. Every time you get the occasion, remind people of the limits and costs of the deathly project of generalised AI. In these lines, I only mentioned its effects on my job as a translator, but the consequences in other fields, such as education, are absolutely catastrophic. Everywhere, this sinister project must be fought every step of the way.

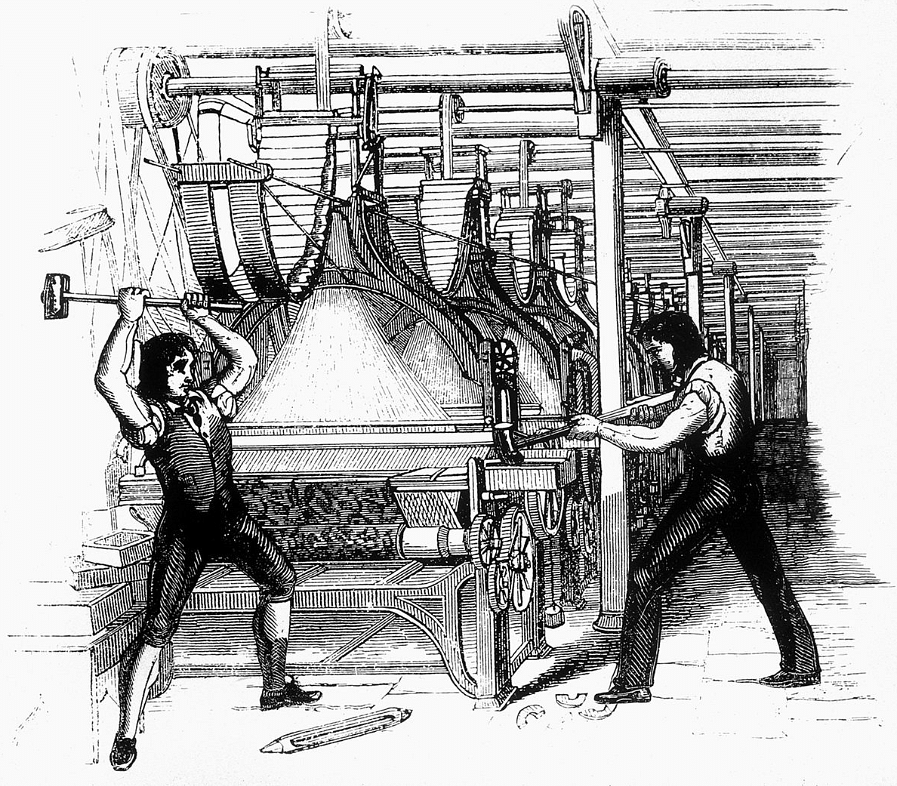

AI isn’t the future. It is one vision of the future, pushed by a handful of oligarchs for their personal enrichment at the expense of the rest of humanity. To paraphrase an excellent comic by Tom Humberstone: is this is our future, then we must sabotage it.