This cryptic title is the abbreviation used for the activity I’ve been busy with for the past months: localisation (L + 10 letters (count them!) + n — clever, innit?) But what is localisation? Mainly, it is the name given to software, videogame and website translation. Why a different name? Because although localisation is a form of translation, with all the cultural adaptation it entails, it has technical specificities which I will discuss briefly.

First, a bit of context: last January, Warlocs, an independent collective of translators, were kind enough to entrust me with the translation of Not Tonight 2. In this game, you play three friends travelling across dystopian United States to save a fourth one who was captured by a group of quasi-Trumpian extremists. To fund their journey, they work as bouncers: the core gameplay is time-limited document verification, inspired by the most excellent Papers, Please.

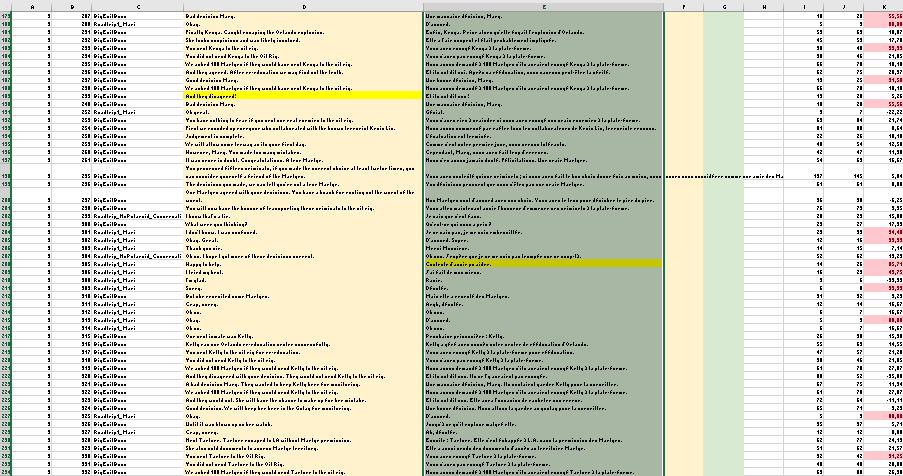

So I enthusiastically dived in the pages… or rather the files. As usual in this field, some 70000 words were sent to me as spreadsheets, where each line can represent a bit of the interface, a narration paragraph, a dialogue line, etc. It is a bit daunting at first, but you get used to it. During the translation, I encountered three main difficulties that were specific to localisation.

First, the character limits. The expansion rate, well-known to book publishers, must be watched very closely when localising. For instance, a book in English usually grows by 10 to 20% when translated into French. Although it is acceptable for dialogue lines, it can be absolutely impossible for UI elements which have only limited space (see for example how many letters there are in the French translations of “run”). That’s why in the picture above, there are three columns on the right side which I use to count the number of characters in English, in French, and the expansion rate, which turns red when it goes above 10%. I was always watching it when translating.

Next, the problems with spreadsheets themselves. Translating a text is usually quite linear, but it’s not necessarily the case here: the authors’ texts, often written with other tools, may appear in an arbitrary order once converted to spreadsheet format. Some dialogues must then be translated out of order, which makes any form of consistency and flow hard to achieve. Another issue: the identifiers of each line (Who is speaking? In what scene?) can lack clarity or contain errors, which means you have to be extra watchful. Thankfully, the developers had given us a beta version of the game to help us evaluate the context of each line, but it is a luxury that most localisers are not given.

Finally, you can’t always translate everything. Although the spreadsheets contain most of the game’s texts, it’s sometimes not the case for words appearing in background pictures. Let’s take an example from Not Tonight 2: there is a cult called “the Creed cult”, which you could translate by “la secte du crédo” (“crédo” is “creed” in French). However, the word “Creed” was present in the level background, and not translatable, so I’ve had to keep it and work around it. My translation then became “la secte Creed”, while its members, the “Creedsmen” in the original, became… “les Creediens”. I like this translation because it has religious overtones — “Creediens” sounds like Chrétien (=Christian) in French — but I might not have used it if I could have translated everything.

There are ways to prepare all the game’s elements for them to be translatable (this process is known as internationalisation, or i18n — i + 18 letters + n — can’t get enough of this). It is not always possible, however, or even desirable, and it can represent an unwelcome cost for a small studio.

Localisation implies quite a few more constraints: one among these (which I didn’t have to deal with in this case) is translating lines that will be recorded by actors, which entails all sorts of problems that audiovisual translators know well. In the end, although all these parameters sometimes feel like you were given an impossible mission, localisation is a fascinating job, and one I really love. I will have more occasions to write about it, and to dive deeper, because I will work with the Warlocs on several more projects. In any case, if these few words allowed you to have a quick look behind the scenes, be sure to be indulgent next time a localisation seems a bit off: the translator has surely done everything they could!