On this blog, I would like to write about the translations I’m working on, both to show how the sausage is made and to bring myself to explain my translation decisions. This way, I’ll be able to further convince myself — and maybe you too — that they are relevant. (At a given time, of course: you always find fault with a translation you come back to later on.)

I’ll start then with the translation I’ve worked on for my Master’s degree: The Breath of the Sun (Aqueduct Press, 2018), by Isaac Fellman. There were several difficult aspects to this book, and I wasn’t sure which part to present here. The short-lived (and dishonest) crusade against the French neutral pronoun “iel” (which you can read about here) helped me decide, since I did use the infamous pronoun in my translation.

First, some context: the narrator, Lamat, has recently met Disaine, a scientist and former priestess. Disaine wants to hire Lamat as a guide to climb the mountain sitting atop of their world, the top of which, legend has it, goes beyond the stratosphere. Lamat belongs to the Holoh people: this mountain is a god to them, and they can’t climb it without respecting some complex ceremonies. Disaine implies that Lamat hasn’t had much trouble breaking her people’s taboos.

Here is her answer:

The original (p. 14):

“It wasn’t that,” I said, and looked over the basket at the side of the mountain, with its billion footholds in the snow. Snow on God’s body, dry and fine. “It wasn’t easy to break at all. But I thought — and I still think, even though it was such a disaster, even though people died and marriages ended…”

“Yes?”

“I grew up being told that God doesn’t want us to climb. That we wound Them with our feet, that we blood Them with our fingernails. And that I’m not sure it’s true. The Holoh are the only people who are visible to God. Why would They choose us, if not so that we could someday see Them face to face?”

My translation:

– Ce n’est pas ça », ai-je répondu en regardant, derrière la nacelle, la montagne et ses milliards de points d’appui dans la neige. De la neige sur le corps de Dieu, sèche et fine. « Ça n’a pas été facile du tout. Mais je me suis dit – et je me dis encore, malgré le désastre, même s’il y a eu des morts et des mariages brisés…

– Oui ?

– On m’a toujours dit que Dieu ne voulait pas qu’on grimpe. Que nos pieds Læ blessaient, que nos ongles L’écorchaient. Et je ne suis pas sûre que ce soit vrai. Les Holohs sont le seul peuple visible aux yeux de Dieu. Pourquoi nous choisirait-Iel, sinon pour que nous puissions un jour Læ voir en face ? »

Lamat uses the singular “They” to talk about God/the mountain, and the capital T reinforces the divine character of that being. Her using it is all the more interesting since Disaine uses “He”, the male singular pronoun, to talk about that same god. Theological discussions are frequent in the book, and it is important to render them in all their nuances. There is thus no way I could neutralise this difference in French and have both characters use the masculine singular pronoun il, all the more since gender is a central theme of the book.

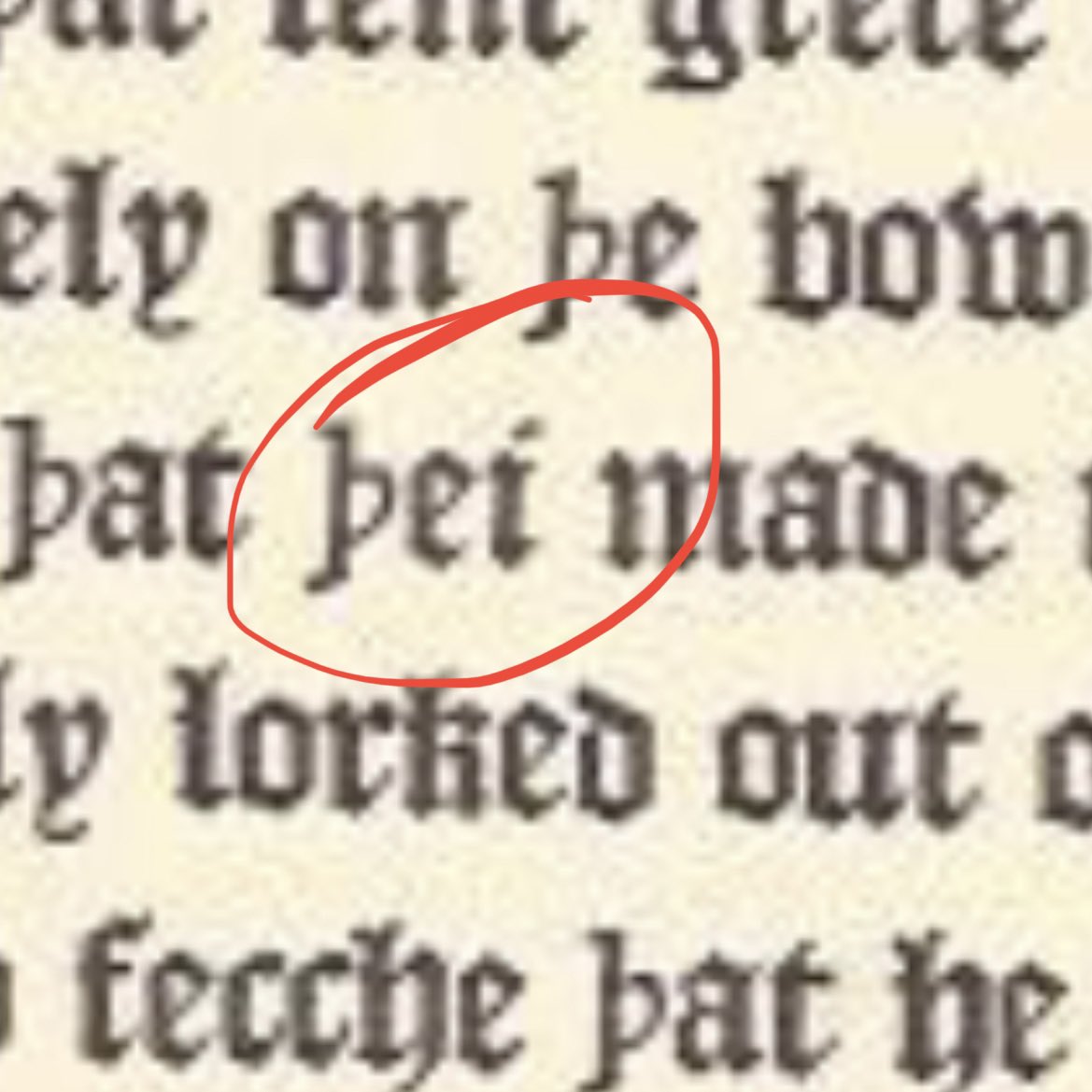

At this stage, the translator worries. How are you supposed to translate this, in a language supposedly so hostile to gender-neutral terms? If using the singular they is perfectly appropriate in English (since at least 1375, the Oxford English Dictionary tells us), French is sorely lacking in the neutral pronoun department… at least that’s what I thought. Further research in the matter brought me to iel, of course, but I’ve also encountered ael, al, el, ol, ul, yel and even ille. Some of these are regionalisms, some already existing in Middle or Old French while some others are more recent creations, but there are many possibilities.

However, these are pronouns that few French readers are used to encountering. My translation would then automatically feel unfamiliar in a way that the original doesn’t, which is why I decided to use “iel” so as to make that discomfort minimal: a French reader understands it is a mix of il and elle, and it sounds common enough in French to not sound too alien.

That being settled, I still had to deal with “Them”. Again, the translator worries. It would indeed be regrettable to use the gender-neutral pronoun iel only to then pick the gendered objet pronouns le or la which would bring back Lamat’s neutral god to a male or female gender. More research led to more discoveries: I had at my disposal object pronouns such as Lo, Lea, Lu or even Lae. Lamat’s people feeling tradition-oriented and speaking a language that is somewhat archaic, I opted for using Lae and adding a ligature to get Læ (rather rare in French, tied letters mainly appear in borrowings from Latin, which gives this pronoun a more historical feel).

This aren’t necessarily pronouns I use on a daily basis. I seldom read them, and hear them even less frequently, but I felt they would be the most appropriate option for this text. Of course, a reader who has never come across them will probably stumble at first: they will wonder briefly what iel is referring to, how to pronounce læ… But they will also perceive another aspect of what differentiates the two main characters, and it is my hope that they will understand better the book and its world because of this decision.